When the EU passed the General Data Protection Regulation in 2016, it immediately cemented 2016 as a landmark year in both data governance and the internet itself, due to the gargantuan implications of one of the world’s foremost economies passing actual, substantive data regulations in light of the discovery that major companies were recklessly sharing user data with third parties for profit.

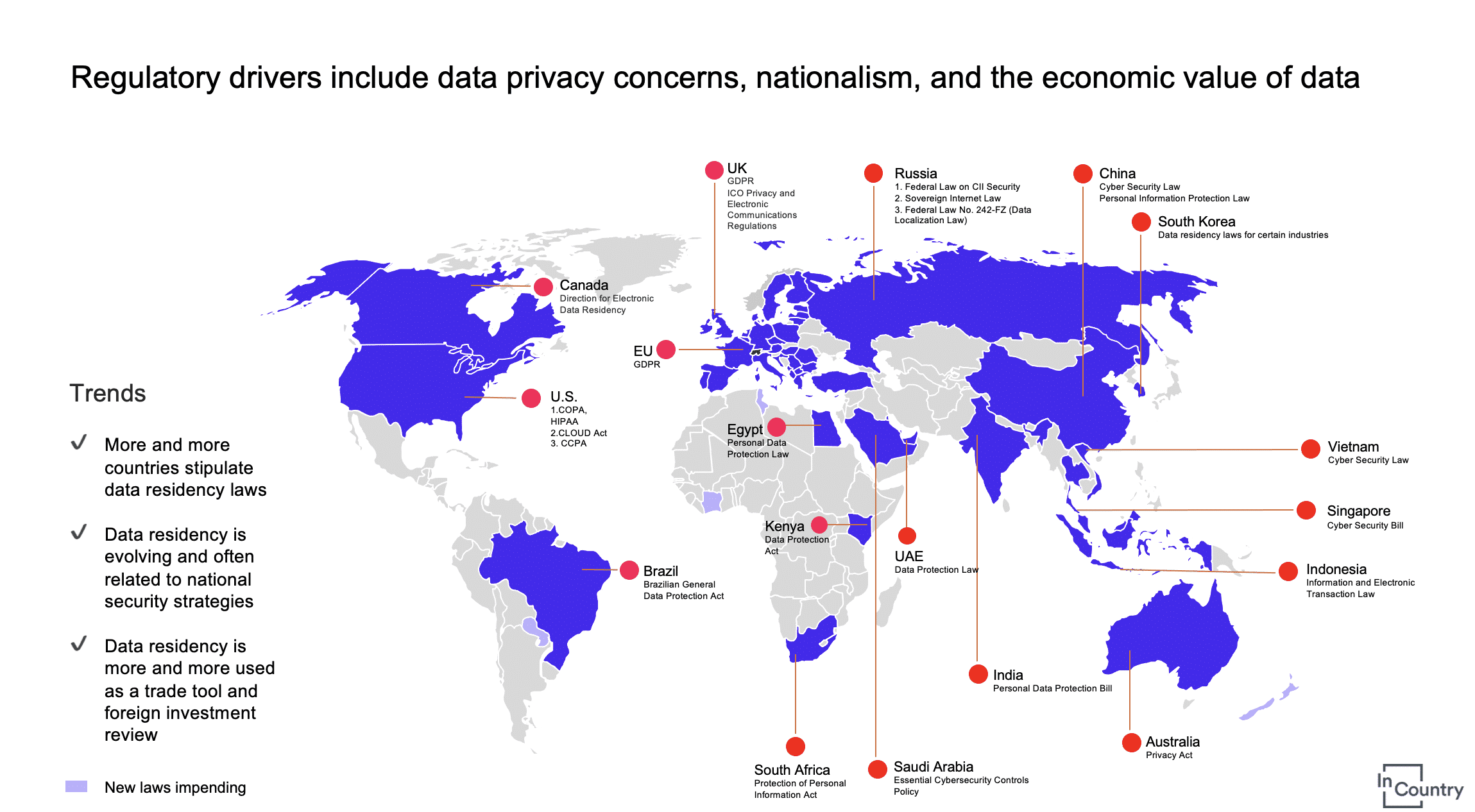

With a flurry of data regulation legislation either passing or coming into the mainstream conversation over the past year, 2021 will also go down as a watershed for data governance and the internet as we know it. As of now, countries both big and small from every inhabited continent on the planet have turned to data regulations to both protect their citizens’ data and to catch up with the evolution of the internet, trying to morph the sphere into a more manageable entity.

In 2021 alone, China, Russia, Saudi Arabia, Turkey, Kuwait, the UAE, Uzbekistan, and Kazakhstan all passed either laws or amendments to laws on data protection regulations. Meanwhile, India, Indonesia, and Vietnam all have comprehensive data protection bills pending, with all the latter two expected to become law within the next 6 months. The United Kingdom also needs to get its data protection situation in order after Brexit and the eventual EU decision to grant their neighbors across the Channel a 4-year grace period for compliant data flows; while the UK does have its own data protection law, leaving the EU will force certain deviations from the GDPR. That list, combined with the EU nations covered by the GDPR, means that nearly all of the world’s 30 largest economies have some form of data regulations in place as 2021 winds to a close.

With so many countries passing their own data protection legislation, many of which are embracing data localization, which requires sensitive data to remain within the country of origin and essentially shuts down cross-border data transfers, onlookers are worried that the internet will soon look more like a jigsaw puzzle than a single canvass, with each country segmented in its own bubble. While data protectionism could indeed pose a problem, and research has shown that the trend is harmful to both global and domestic economic growth in the long-run, the rise in data localization policies by itself does not signal the imminent emergence of a segmented internet.

China’s Great Firewall is simply too large and hasslesome a project for all but the world’s most powerful economies, so we won’t see imitations suddenly pop up. The only throughline for worry in 2021 came in the form of Russia recently passing a law that mandates big tech companies to open physical offices within Russia, similar to a Turkish law that originally contributed to chasing PayPal out of the country. China itself has long had a law on the books that prohibits foreign entities from owning and operating their own data centers within the country, which is why AWS and Microsoft Azure run through a Chinese-branded intermediary. These laws do not seem overly preoccupied with controlling big tech outright, but rather seeing if they’ll come to the table and oblige foreign governments on certain matters. The heavy-handedness is not ideal, but it hardly indicates a looming threat to the internet at-large, especially when even Western democracies have had it with big tech.

China took center stage on data regulations in 2021, passing several data-related laws and rules on data transfers, headlined by the comprehensive Personal Information Protection Law (PIPL), which passed in August and took effect soon after on November 1st. The main commonality between all the year’s Chinese legislation has been data localization and limiting large companies from freely running data streams, creating an immensely challenging compliance landscape that Yahoo and LinkedIn have already willing opted out of. Things have settled in recent weeks however, with most companies seemingly set to test out the waters before giving up on the world’s largest continual growth market.

Amidst the Covid recovery, the Middle East has begun to resume its regional plan to remake the economy by 2030, shifting from oil to fintech. Accordingly, Saudi Arabia and Kuwait’s new data protection laws favor strict data localization, and although the UAE’s new data protection law, set to come into effect on January 2nd, 2022, does not require strict data localization, the country’s rush to get the law passed is significant. These mandates are coming from a different point of view, as the countries seem intent on protecting the newfound currency of data as a hedge on the billions of dollars the region has invested in fintech startups.

Russia, which adopted data protection legislation, Federal Law No. 152-FZ, over a decade ago and before most nations had even begun to consider the issue of data flows, has spent 2021 battling social media and big tech for control of data. The country notably is requiring big tech to open offices within Russia, but it has also repeatedly fined these companies for various violations and increased the fines it can hand out per data violation.

Former Soviet countries Uzbekistan and Kazakhstan, having important relationships with Moscow, also amended their previously feeble data protections to include data localization mandates and better enforcement mechanisms. Systems do not seem fully set to capitalize on these changes completely, but the notion of doing so is a monumental enough change for Central Asia.

India, another of the world’s largest economies, has also continued to talk out a comprehensive data law, although governmental debate has happened before and gone nowhere. What is different for India in 2021 has been the gusto which they went after several companies, including Mastercard, for violations of the Reserve Bank of India’s data governance requirements. While that specific legislation is sector-specific to payment cards, using data regulations as a legislative tool against international corporations is a new for the country, giving many the expectation that this time a comprehensive data protection law will soon manifest.

Data governance in Africa is behind where it is in most places around the world, but the issue is picking up and has room for substantial development. This year Senegal passed a law requiring government data to be localized, and although Nigeria scrapped its data protection draft bill in November, the resulting public backlash indicates that the matter will likely have to resurface soon, lest governments face serious pressure from their constituents.

Globally, data governance became a major topic in 2021, with early adopters like the EU still struggling with the full complexities of the matter, China setting a new stage both for how stringent data localization requirements will be as well as how steep fines will be, and countries everywhere rushing to put out legislation to address real concern among average citizens. With big tech occupying a more powerful place than ever online, the response of governments to make data governance a key agenda topic shows that this song and dance will likely continue long into the future.

As the struggle for the internet goes on, the levels of freedom and protection ebbing and flowing for individuals, the ground made around the world by governments in 2021 on the matter will be remembered as one of the most noteworthy periods for data legislation.